The Neurobiology Of Disappointment: The Pain That Lasts The Longest

The neurobiology of disappointment shows us once again that there are aspects of our lives that the brain experiences in particularly painful ways. So, for some reason we don’t know, in those experiences where we lose opportunities or when trust with someone significant is broken, some kind of suffering is generated that lasts longer.

William Shakespeare once said that waiting is the root of all distress, and it may be true. But it’s also true that we often need to hold on to certain things in order to find stability. In order not to lose heart in the face of all the uncertainties of life. So, we often take it for granted that our closest relatives, partners or friends will not betray us in one way or another.

We also have expectations of ourselves, assuming that we will not fail in the areas where we are so good. Or that what we have today will stay with us tomorrow. However, sometimes fate gives a change of direction and our house of cards crumbles. These experiences, defined primarily by a loss of security, are interpreted in the brain as red flags for our survival.

The disappearance of an opportunity that was so exciting for us, being made redundant overnight, suffering an emotional betrayal… These are more than painful events. They are, in a way, blows to the fabric of what was in a meaningful way a part of us. So let’s see what happens in the brain when we have these experiences.

Neurobiology of deception

The neurobiology of deception responds to a recent interest in the field of neuroscience. For many years, psychologists, psychiatrists and neurologists have wondered not only why this emotion is experienced so intensely. One thing that is clear is that disappointments are also part of our personality.

Those who have experienced them often become more suspicious. Disappointments interfere with the search for hope and sometimes make us more cautious about raising expectations involving people. Either way, something has to happen in the brain for its impact to be so obvious. Let’s find out together what science tells us about it .

Neurotransmitters and disappointment

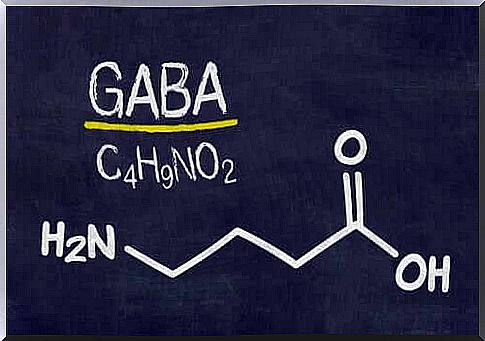

As we know, neurotransmitters are chemicals that transmit signals to neurons. Thanks to this neurochemistry, emotions, behaviors, thoughts, etc. are facilitated. Thus, it is useful to remember that there are very specific neurotransmitters, like dopamine and serotonin. They completely measure our state of mind.

Now, in an interesting study by Dr. Roberto Malinow of the Department of Neurobiology at the University of California, San Diego, researchers found that there are two very specific neurotransmitters that completely regulate the experience of disappointment. These are glutamate and GABA, which act in a very specific area of our brain: the lateral habenula.

Habenula and the release of GABA and glutamate

The lateral habenula is one of the oldest structures in our brain. So we know, for example, that it is part of the emotional processes that facilitate our decision-making. However, despite the fact that it often acts in a positive way, boosting motivation, this region also has its dark side.

Its proper functioning essentially depends on a correct and balanced release of glutamate and GABA. Thus, the greater the contribution of these neurotransmitters to the habenula, the greater the feeling of disappointment. On the other hand, the lower the release of GABA and glutamate, the less impact this emotion has on our brain.

Depression linked to the neurobiology of disappointment

Dr Roberto Malinowski, quoted above, makes an important point about the neurobiology of disappointment. We have seen that the impact of disappointment sustained over time leads in many cases to depressive disorders. That is, when the release of GABA and glutamate is intense, there is a greater risk of suffering from this psychological disorder.

We also know that this excitement of the habenula due to the excessive release of these neurotransmitters makes us more obsessed with certain ideas, memories or painful situations experienced. It is very difficult for us to turn the page, hence the emotional stagnation and suffering.

However, the discovery of the relationship between glutamate and GABA in disappointment and depression also opens the door to new treatments. Until now, it was assumed that thanks to antidepressants and serotonin regulation, the GABA-glutamate ratio was also balanced. Today, however, it has become evident that despite the improvement, it is common to experience various side effects.

The current challenge is therefore to develop treatments which act specifically on certain neurotransmitters and not on others. In this way, more appropriate responses would be given to patients who, due to various alterations at the neurochemical level, experience certain realities more intensely. The neurobiology of deception is therefore an area of great interest, the understanding of which we are gradually improving.